The epic opening words of Charles Dickens’ classic, A Tale of Two Cities, brilliantly introduces the contrasting experiences of the characters associated with the two great cities of the day, London and Paris. One city speaks of freedom, hope and peace, the other of tyranny, oppression and vengeance.

The cities

When we come to the Old Testament book of Daniel, we find that it begins in a strikingly similar way – it’s a tale of two cities. Except this time it’s not London and Paris, but Jerusalem and Babylon. And again, the cities are not merely places where people live but metaphors, representations of two different ways of life. These two conflicting value-sets, opposing philosophies or ‘world-views’ are derived from what these two great cities stand for.

Jerusalem

Jerusalem was the capital of Judah, the southern “half-kingdom” of Israel after the nation split around 922 BC. By the time the Babylonian armies arrived in 605 BC, much of its former glory was diminished. It seemed like an insignificant place, except for the promise of God, “I have chosen Jerusalem, that My name might be there” (2 Chronicles 6:6 – emphasis mine).

Jerusalem was intended to be a city not like other cities. Not somewhere where a man reigned, but somewhere where God reigned. Things were to be administered according to His principles; life was to be governed by His laws. God placed the line of kings there, but their purpose was not to rule according to their own preferences, but according to His will. Many of them abandoned their mandate and served themselves rather than God. But still, in spite of their failure, Jerusalem remained “the city of our God” (Psalm 48:1).

Babylon

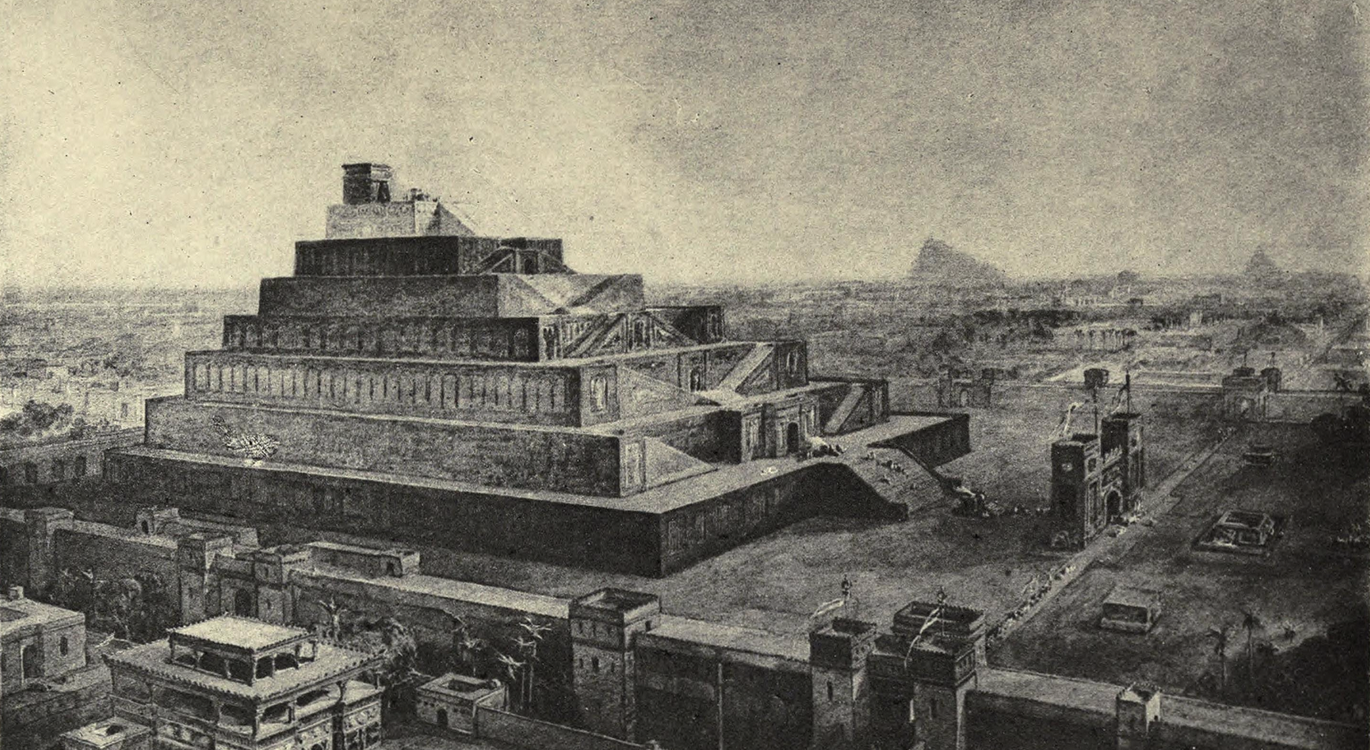

On the other hand, Babylon was the capital of the empire, the centre of geopolitical power. The Bible first introduces us to Babylon way back in Genesis 11. There, the declaration of the builders was, “let us make a name for ourselves” (Genesis 11:4 – emphasis mine). The purpose of this city was in total contrast to the purpose of Jerusalem. Here, mankind ruled supreme, God and every value He had determined were set aside. As long as a person lived within the framework determined by society, they could do as they pleased. These statements could just as easily apply to modern Western cultures as they do to ancient Babylon. The spirit of Babylon is alive and well today.

And so, this centuries-old story, unfolding in an ancient and far-off land (unless you live in modern day Iraq!) contains profound lessons for people living in a contemporary culture.

The world-views

As the narrative develops, we are introduced to a variety of different people living under different governments which operate different systems. Everything is constantly changing. And yet, nothing really ever changes.

For all the different monarchs and their different kingdoms, when everything is distilled down to its simplest form, there are really only two ways of life, only two world-views – one where God is God and one where self and selfish desires take His place.

The self-centred world-view

This second world-view manifests itself in many different ways – Nebuchadnezzar (chapters 1-4) is arrogant, and motivated by power, ambition and a lust for his own glory. Belshazzar (chapter 5), on the other hand, is driven by pleasure, sensuality and desire. Though very different men, they are simply expressions of the same thing – a mind that has replaced God with self. It is a secular mindset, where anything that is spiritual is closed off; a humanistic mindset, where mankind and human intellect replace God and divine revelation; a naturalistic mindset, where only what is physical is considered of any value. And it always ends in ruin.

The God-centred world-view

Contrasted against this self-centred mindset throughout the narrative is one man (along with three of his friends). He is an expression of the first world-view, where God is in His proper place, worshipped and revered. He doesn’t live for what makes him happy. He lives for what is true. And the wonder is, that living for what is true is the only way to be truly happy.

The man

Our protagonist is Daniel. He has been abducted from his homeland and taken to Babylon as a teenager where he has been castrated – robbed of any future hope of ever having a family. As far as we know, he will never return to his homeland.

And yet, Daniel stands tall among the giants of faith in the Old Testament, only one of a handful of significant characters with no criticism recorded in Scripture. In the book that bears his name, only two things never change – Daniel’s character and Daniel’s God. His character does not change because his convictions and source of strength are rooted in his God. He is governed by prayer, fashioned by the word of God.

Daniel lived in the same world we live in. Yes, it was 2,500 years ago. Yes, science and technology have changed it beyond recognition. But Daniel’s challenges are our challenges. The struggles he faced, we face too. And the source of his triumph – God – is our source of triumph too.